A Swiss Volunteer’s Experiences in Idomeni and Lesvos Refugee Camps

I meet Ella in a café near Basel main station. She has short, wavy brown hair and wears a skirt and blouse in pastel colours. It is a sunny Friday afternoon at the end of May and everybody seems to be happy that summer is finally coming. The café where we meet is at the edge of a park with little children playing in the small basin. In this environment, refugee camps seem to be something of another universe.

But not for 24-years-old Ella who holds a BA in History and Law from Basel University since February. Since she can remember she has been interested in sociopolitical and migration issues. While she was looking for a job and thinking about taking an MA, the media images from Greek refugee camps made a deep impression on her. After having a look at fluechtlingshilfe.ch to see which organization would fit her, Ella packed her bag and within one week she took off to Greece, in order to help people on the ground, and gain some working experience:

“Especially after studying European law for my final exams, and because in general I think that human rights are a great achievement for our society, I was shocked that nobody seemed to care and many guarantees from international law were ignored. So I thought: I have to go to Greece if I want to keep respect for myself.”

Cooking for 1000 People

She arrived in Lesvos the same week as the treaty between Erdoğan and Merkel went into effect and the island was evacuated. The NGO she worked with supported people who headed to mainland Greece by ferry. Every morning in the square house, her team sorted out the donations from Switzerland such as clothes, diapers or baby products and made packages for the night shift team. Later they went to the port and distributed food, clothes or baby products but especially water which is very expensive on the ferries. The second team did night shifts to receive the incoming refugee boats and to distribute clothes, dry shoes, hot tea and some food. Ella was shocked that nobody on the island had been informed about the evacuation. But also the Greek police and even Frontex were often only informed some hours before on what they should do.

Since fewer volunteers were then needed in Lesvos, Ella went to Idomeni for 2 weeks and later returned for another 3 weeks joining a second organization from Norway. The first project she participated in concentrated on food distribution since that was the most urgent problem. “But it was not like we were distributing food as if feeding chicken with grain, as a refugee formulated it.” The volunteers bought ingredients and cooked together with the Syrian women. The cooking took about 2 or 3 hours every day. Ella remembers the food distribution to around 1000 people as an intense procedure, as you always had to make sure that everybody got the same amount of food and that nobody cut the line. But it was also a fulfilling task because one could almost feel like in a ‘normal’ household instead of a refugee camp.

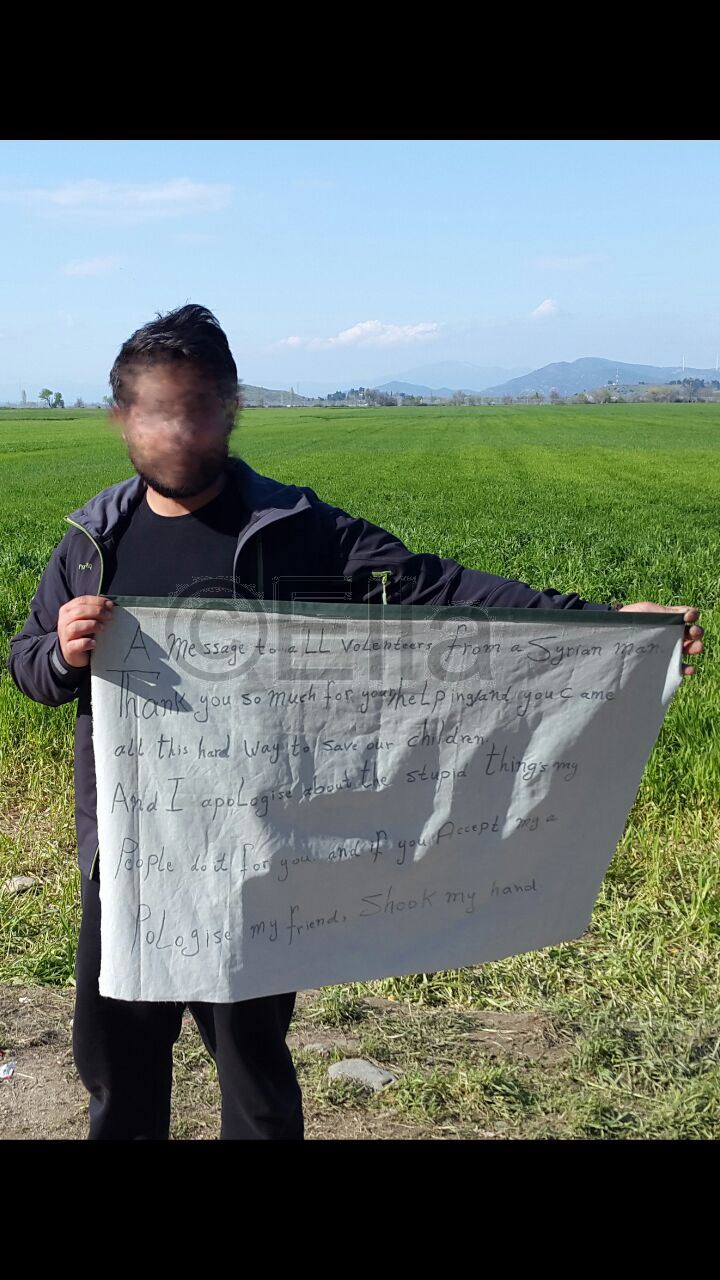

“After some time people knew you and had respect for your work, especially because they finally understood that you are an unpaid volunteer who takes a break from normal life only to help them and who even spends money for that. This was not clear for them in the beginning. But after a while we also started talking about private issues, for example they invited me to their tents to have tea and to chat.”

Around 10 p.m., the volunteers would usually get back to the expressway hotel where they stayed. It turned out to be rather difficult to find accommodation in this rural area. Most of the available rooms were already rented out to other organisations or media workers, sometimes at exorbitant prices. There were many different organisations of all sizes and from different countries in Europe present on the island, some large and internationally known NGOs, but also the Spanish lifeguards and the Catalonian firefighters. Ella worked with an organization of around 10 members. But there were also people who came to the island independently with a car packed with donated goods. At a local hotel, about 20 organisations met regularly to ensure better coordination.

How to work under extreme uncertainty

The second organization Ella joined worked in a military camp in Polikastro near Idomeni where they distributed sanitary products, clothes, diapers or baby strollers since the military was already in charge of the food. Here too, it was important for camp residents to know that the system was reliable and that there were enough supplies for everybody. In the beginning, Ella found it difficult to stay calm in certain situations, for example when people started talking in a loud voice or pushed each other during food distribution:

“It is nothing personal, it is just another culture. As if we were in a bazar. So I don’t get angry if he asks me every day if he can’t take four portions of food instead of one because it is normal for him. I understand that he doesn’t want to queue up with his whole family. But I have to guarantee that there is food even for the last one in the queue so I have to insist on the rules and be consequent in the individual case for the benefit of the others. But this is something you learn.”

Furthermore, Ella also learned how to work even under the most uncertain situations without much time to rest, such as during demonstrations or hunger strikes when you never know how the situation will evolve. But she also got more understanding for the Syrian culture:

“Of course, here are also many people with a migration background but there you are the individual from Europe in a community where all women wear headscarves and find it unbelievable that you are not married at the age of 24 but live with your boyfriend and don’t have children (laughing).”

Happy and Sad Moments

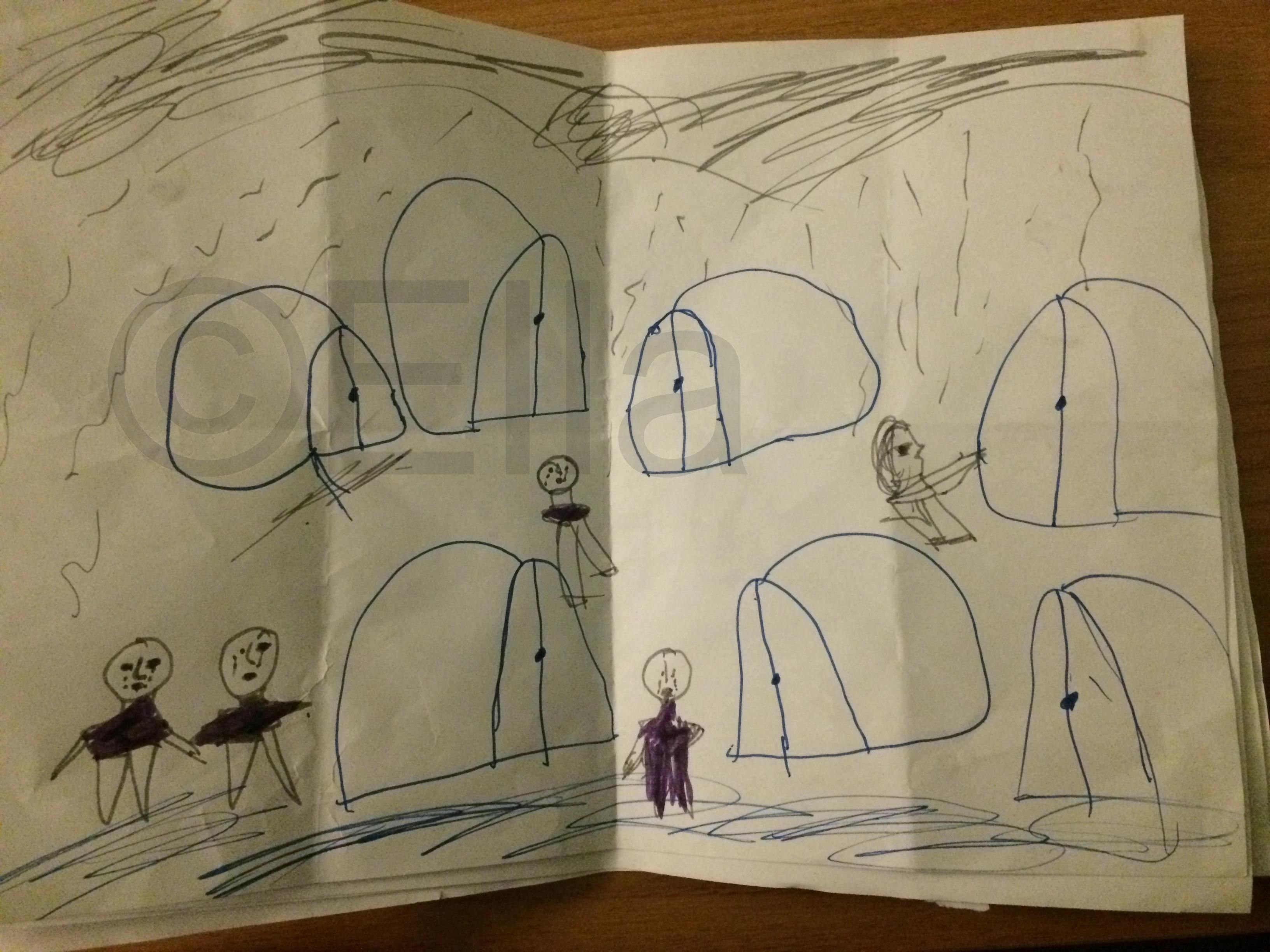

It was interesting to experience how you can communicate without words, relying simply on gestures. Although, when necessary there was always somebody who was fluent in English to translate. The children, however, did not need a common language to take Ella to their parents who were happy to have a little talk. But even in the happiest moments, the refugees’ terrible memories were never far away.

“It is impressive how people can be so open and welcoming although they have gone through terrible situations which come to the surface in a normal and joyful moment. Situations we only know from war movies and don’t expect to come up in such moments. It completely destroys the illusion of normality. At the same time it meant a lot to me that they trusted me enough to share their stories with me. Just being there and listening already meant a lot to them, but of course you often wish you could do more.”

After working so closely with the refugees during her first stay, Ella returned to Idomeni. It made a big impression on her that many people remembered her name when she returned, although she couldn’t remember all their names and they had obviously seen many volunteers in the meantime. But returning was not only a joyful experience.

“It was sad to see how people had changed. For example families who had tried to cross the Macedonian border up to eight times. But they never succeeded and were deported back to Greece after some days. And you know exactly that even if they get to Macedonia they will never get to Serbia. So you try to cheer them up, but then they go again and come back some days later. Also the children got quiet and laughed less than before. Sometimes it didn’t take long to cheer them up but I still noticed their desperateness and resignation.”

After all these experiences, coming back to Switzerland seemed sometimes completely surreal, so Ella was grateful she is able to talk to her friends. “You get back to your daily life in Switzerland very fast, but at some moment it seems absurd to you and you only want to cry.” She keeps contact with refugees from Idomeni, but being a student without much financial means or political influence to help them is not always easy, she says. But at least it is a valuable experience for them and for her to see that both sides are interested in staying in touch. She plans to go back to Greece, but holding a BA in Law she is also thinking what else she could do. “I realized that I want to do more than that and find a job in Basel were I can achieve more than just meeting basic needs.”

Experiences for a Life-time

To sum up, Ella’s trips to Greece has been a very valuable experience. She hopes that as many people as possible would personally experience what happens in the refugee camps in Greece.

“Not just the terrible images from the media. Because there are many more aspects then just those muddy tents. There are also beautiful moments which show you the absurdity of the situation but also how small things can mean something, how you can encourage somebody simply by treating him or her as a human being and not just as a number.”

To prospective volunteers, she recommends to have a good look at different organisations working in the camps on the internet before travelling to Greece. Although it is also possible to travel there individually and find out how you can contribute on site, as daily tasks are published at blackboards. Especially long-term volunteers are needed to ensure some continuity in the aid provided. But above all, she hopes for a pan-European solution as soon as possible:

“The conditions in the new camps are inhuman, especially in summer. There is not much shadow or air circulation in these camps and this is dangerous for small children and elder people because temperatures can reach over 40°C. Not to mention the lack of sanitary facilities or water supply. Also for children it is important to go back to school since they haven’t been to school for months or even years. They have to settle down somewhere. Also the adults have to get back to work to keep their dignity

The interview was conducted by: Yvonne Siemann

Yvonne Siemann

is a PhD candidate at the University of Lucerne. Her thesis deals with Japanese descendants and their identity constructions in Santa Cruz, Bolivia.

Within the IMISCOE PhD Network Yvonne is a member of the soundboard and editor and contributor to the IMISCOE PhD Blog.

All pictures © Ella.